Garganornis: The Mother Of All Geese

Geese are already bloody scary, now imagine running into one that was three times the size, had bony knobs on its wings, and was even more hot-tempered? Terrifying, right?

It’s a bright, sunny morning on the island of Gargano - an isolated mountain massif that will, in just a few million years’ time, join mainland Italy. There’s not a cloud in the sky, yet the dawn air is filled with the sound of thunder. This is no regular thunder though, between each deafening clap there are rasping hisses and blasting honks, enough to make the island’s sabre-toothed deers head for the forest, pygmy crocodiles for the shallows, and moon-rats for their burrows. There’s breakfast to be had, but no one is bold enough to cross the beach while its rowdy occupants wrestle in the sand. There are hundreds of Garganornis here, and it’s mating season.

You wouldn’t say boo to this goose

There are few things more fear-inducing than an advancing goose, its wings flared and neck bent low, hissing as it charges at your shins. These long-necked, steely-eyed devils have garnered themselves quite a fearsome reputation, not just amongst us humans but amongst other animals many times their size too - cows, elephants, tigers and even gorillas have all been seen retreating in fear after a particularly feisty face-off with a goose.

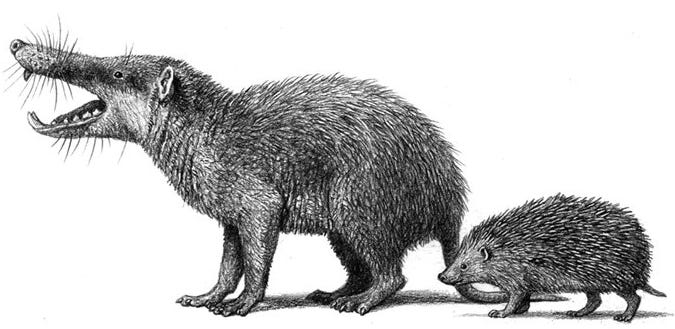

The giant Canada goose, Branta canadensis maxima, is the largest goose around today, with a wingspan of up to 6 feet and a reported maximum weight of around 9kg. While big, these geese would have been dwarfed by Garganornis, perhaps the biggest waterfowl that ever lived.

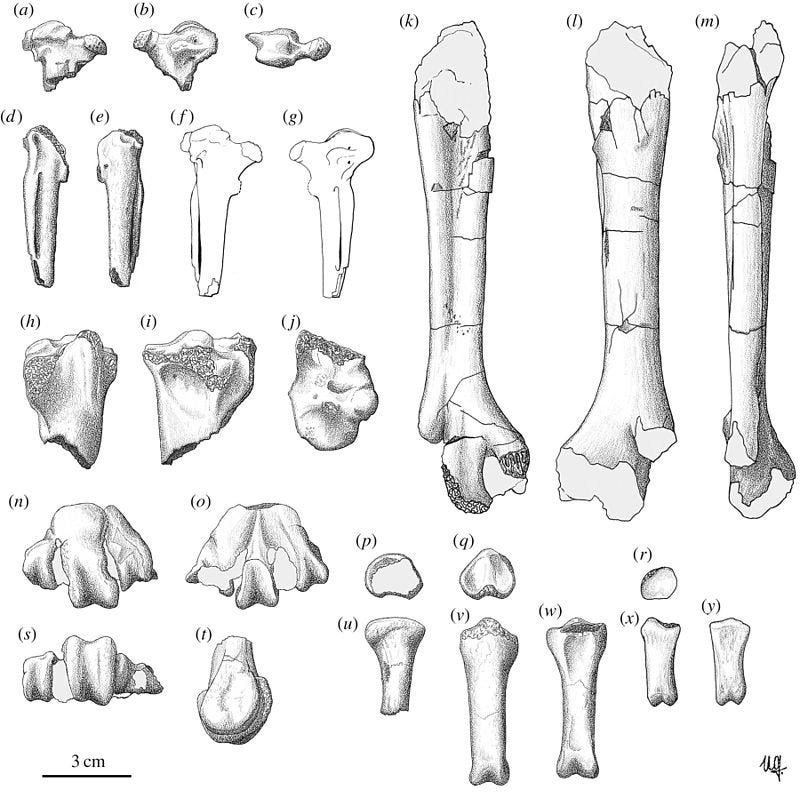

This extinct genus of giant anatid isn’t known from a lot of fossilised material, largely fragmented arm/wing, leg and feet bones, yet researchers have been able to estimate its size by comparing its bones with those from mute swans - one of the heaviest living waterfowls. From these comparisons, researchers estimated that Garganornis may have weighed as much as 23 kg, which is just a bit lighter than an adult emperor penguin. At 1.5 m tall, however, they’d have looked down on these 1.2 m tall, antarctic birds.

Unlike its modern-day relatives, geese, swans and ducks, Garganornis couldn’t fly. This isn’t too surprising, considering its sheer size, and it was the bird’s bulk that originally led researchers to this flightless conclusion. Further analyses of Garganornis’ diminutive carpometacarpuses (lower wing bones) have confirmed this conclusion, as have some stout posterior phalanges (toe bones) that suggest the bird would have lived a wholly terrestrial lifestyle, with no trips to the skies and few, if any, to the water either. This is a very different way of life to that which we associate with geese, swans and ducks of today.

Garganornis would have no doubt shared the same aggressive anatid attitude as its extant relatives, though. In fact, researchers have reason to believe that it may have been even feistier, due to the presence of some specially-evolved wing weaponry. On their short carpometacarpuses, Garganornis sported small, bony knobs. These adaptations have been observed in living relatives of Garganornis and are always used as weapons. A fight between two of these oversized waterfowls could have easily broken bones or, in some cases, even resulted in death.

While it may have been hyper-aggressive, like living geese Garganornis was a strict vegetarian. Taking into account its bulk, flightlessness and terrestrial lifestyle, researchers have suggested that it filled the role of a large, herbivorous grazer in the island habitat that it lived. This is a niche that is typically occupied by large mammals, like elephants, rhinos and bison, in mainland habitats. How this giant goose evolved to outcompete its mammalian rivals and become its island’s dominant herbivore can be explained by the bizarre biological phenomenon known as island gigantism.

There be giants on those islands

Garganornis means ‘Gargano Bird’. Gargano is now a region of mainland Italy, but during the Late Miocene - the time in which Garganornis was in its heyday - it was an island surrounded by the Mediterranean sea. Isolated from the mainland, Gargano and another nearby island Scontrone became laboratories for some weird, evolutionary experiments that lasted several million years.

A fundamental driving force behind evolution is geographic separation - when members of the same species are separated by some sort of physical barrier. Over time, these populations will develop differing traits and become so genetically distinct from one another that, even if they do meet again, they’ll no longer be able to breed and produce fertile offspring. This is, to put it simply, how new species are made. And when it comes to physical barriers, nothing separates populations quite like an island does.

In 1964, mammalogist J. Bristol Foster conducted a study in which he compared 116 island species to their closest relatives on a nearby mainland. From his comparisons, he found that some island creatures grew larger than their mainland relatives (insular gigantism), while others shrank in size (insular dwarfism). Almost a decade later, in 1973, Foster’s Rule was coined by the evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen who looked at the results of Foster’s study and outlined the following principles: over time on an island, (1) smaller creatures grow larger as predation pressures relax in the absence of mainland predators, and (2) larger creatures shrink as food sources become limited due to land area constraints.

In the case of Garganornis, the first principle of Foster’s rule is applied. There are other reasons why researchers believe this goose grew so giant too. Firstly, Gargano had no large, mammalian herbivores to graze its grass and other shrubbery, so Garganornis grew into this niche - literally. There’s also a suggestion that it grew so large in order to stave off predation from several huge birds of prey that also called the island home.

Many more of Gargano’s traditionally smaller residents grew to gigantic sizes. The ‘Giants of Gargano’ are often referred to as the Mikrotia fauna and they include the giant barn owl Tyto gigantea, the terrier-sized hedgehog, or moonrat, Deinogalerix, and the golden eagle look-alike Garganoaetus. The latter is thought to have been the top predator on the island and perhaps the only threat to Garganornis, though certainly not a fully-grown individual. There were some dwarfs on Gargano too, like Hoplitomeryx - a sabre-toothed, deer-like ruminant that had five - yes five! - horns on its head.

These animals didn’t arrive on Gargano as giants, or as dwarfs in the case of Hoplitomeryx, they evolved into these frankenstein forms as per Foster’s Rule. But this begs the question, how did their ancestors get to Gargano? There’s a relatively straightforward explanation for the island’s giant birds; their ancestors likely flew there and then evolved into the huge species we’re now familiar with, like Garganornis. That explanation doesn’t fly - pardon the pun - for the island’s giant hedgehogs, hamsters and shrews, though.

From the Oligocene to now, sea levels in the Mediterranean have dramatically fluctuated. There were times when sea levels were low and Gargano and nearby Scontrone were attached to Italy, allowing a lot of the mainland’s land-bound animals to move in via a series of different land bridges. By closely studying the rates of evolution in the Mikrotia fauna, however, researchers have found that most probably arrived on Gargano between nine and eight million years ago, during the Late Miocene and at a time when it was most definitely an island. To do so, they must have rafted across on piles of debris, much in the same way that the ancestors of South America’s rodents are thought to have migrated over from Africa.

It ends in flood

Aside from the giant barn owl Tyto gigantea and the golden eagle look-alike Garganoaetus, most of Gargano’s residents were bound to the island’s landmass, and therefore at the mercy of the encroaching Mediterranean sea.

Towards the end of the Late Miocene, large swathes of this sea dried up during a thousand-year period known as the Messinian salinity crisis. This was caused when the Strait of Gibraltar closed and cut off the Mediterranean from the Atlantic, resulting in an almost complete desiccation of its basin. At this time, Gargano was still an island, but one surrounded by vast, inhospitable salt flats, rather than water.

Then, around 5.3 million years ago, the natural dam blocking the Strait of Gibraltar was breached and the Mediterranean basin was refilled by what is now known as the Zanclean Flood. This flood happened very quickly, at least in terms of geological time, and while it may have wetted the arid Mediterranean and brought life back to the area, it doomed many animals to extinction, including Gargano’s giants. It likely took several years, maybe decades, but eventually the island of Gargano disappeared beneath the waves, its land and unique creatures swallowed by the rising sea.

In the Early Pleistocene, however, tectonic uplift in the Mediterranean saw Gargano and Scontrone rise above the waves once more and, this time, join mainland Italy. They’ve been there ever since, connected to the rest of Europe and its endemic flora and fauna. It’s this ‘resurrection’ of these once-sunken islands that has ultimately allowed us to study their rocks and unearth giants like Garganornis.

It was in 1969 that we first learned of Gargano’s ancient inhabitants, when a team of Dutch palaeontologists discovered deep fissures in the limestone quarries and road cuts that pockmark the region. These fissures were full of fossils, remains of animals that stumbled into them roughly eight million years ago and back when many species amongst the now-famous Mikrotia fauna were in their prime. This stroke of geological luck has provided us with an incredibly detailed snapshot of what island life was like in the Mediterranean during the Late Miocene, as well as a fantastic case study for Foster’s Rule.

Gargano now, even though it lies on the coast, is still a highland, consisting of a wide mountain massif with several prominent peaks. Its highest point, Monte Calvo, lies 1,065m above sea level, while lower areas are covered by an ancient oak and beech forest that once covered much of Central Europe. Many animals have settled here, including a wide range of water birds, birds of prey, deers, boars and foxes. As sea levels continue to rise and parts of lowland Italy disappear beneath the waves, Gargano may become an island once more. Garganornis won’t be here to see its home return, nor will Garganoaetus, Deinogalerix or Hoplitomeryx. Instead, new giants and dwarfs will emerge to rule over the island, and what they’ll look like is anyone’s guess.

Name: Garganornis (ballmanni)

Meaning: Garganornis simply means ‘Gargano Bird’, while the species name ballmanni honours Peter Ballmann, who first described the birds of the Gargano region.

Size: 1.5 m

Weight: 15-23 kg, based on comparisons with extant mute swans which are considered 30% smaller.

Age: Late Miocene, between 9 and 5.5 Ma.

Type of organism: Flightless anatid waterfowl.

Environment: Exposed, open areas on forest margins.

Closest Living Relatives: Anatids like ducks, geese and swans.

References

DeMiguel, D., 2016. Disentangling adaptive evolutionary radiations and the role of diet in promoting diversification on islands. Scientific Reports, 6(1), p.29803.

Halliday, T., 2022. Otherlands: A Journey Through Earth's Extinct Worlds. Random House.

Pavia, M., Meijer, H.J., Rossi, M.A. and Göhlich, U.B., 2017. The extreme insular adaptation of Garganornis ballmanni Meijer, 2014: a giant Anseriformes of the Neogene of the Mediterranean Basin. Royal Society Open Science, 4(1), p.160722.

Van Valen, L., 1973. Body size and numbers of plants and animals. Evolution, pp.27-35.

* Thumbnail image adapted from original artwork by Stefano Maugeri. CC BY-SA 4.0, available here.